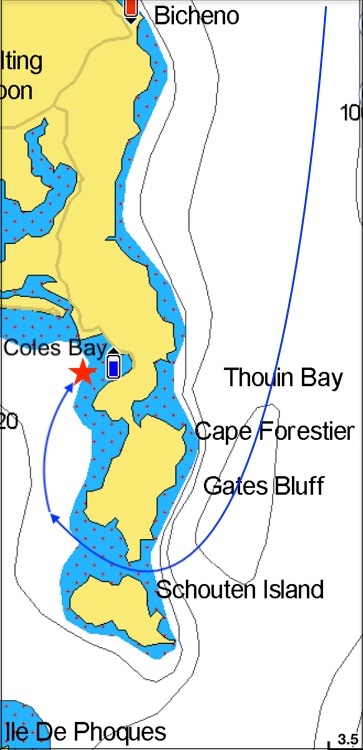

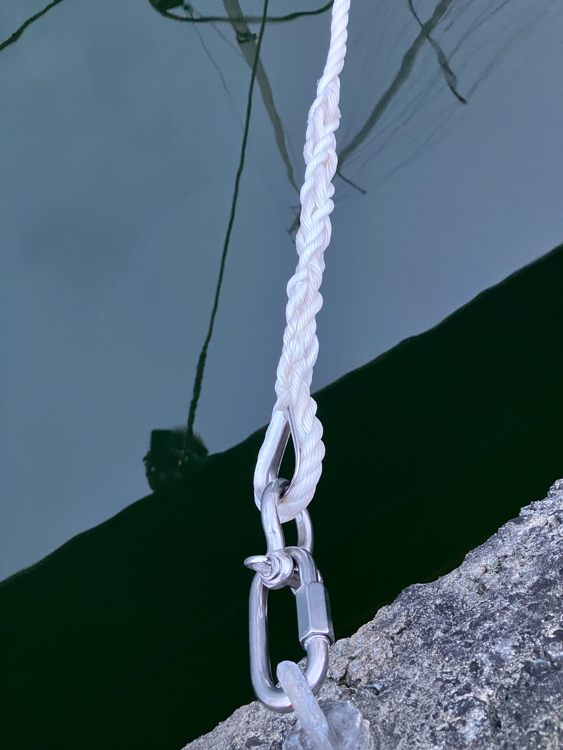

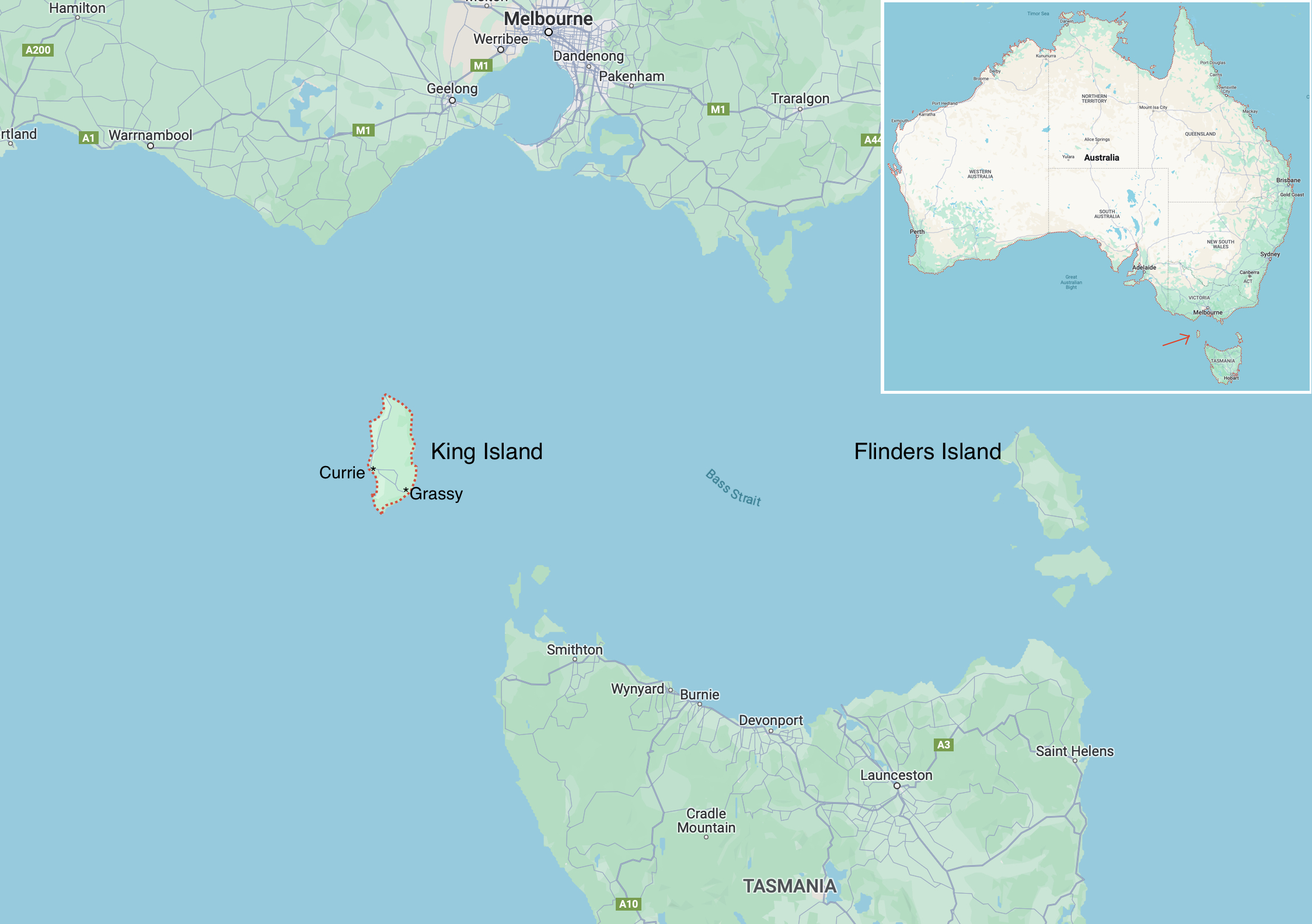

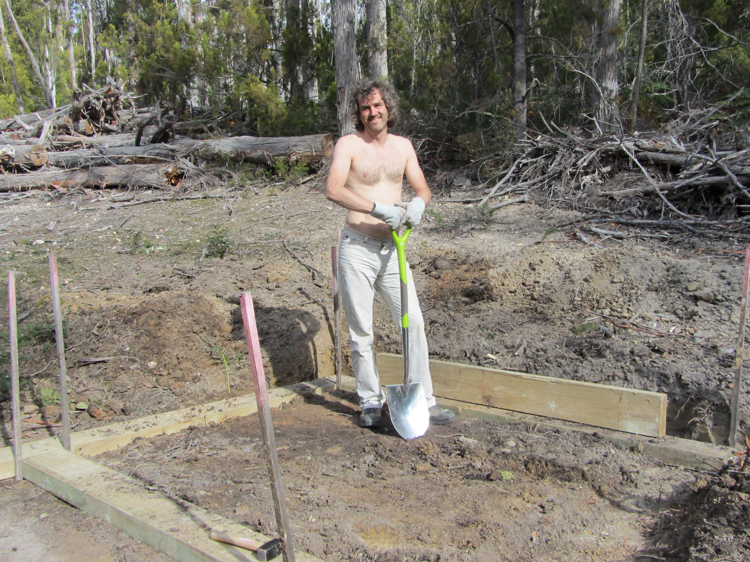

We were on a mooring in Coles Bay, following our crossing of the Bass Strait. After breakfast ashore, we had a crew change. Brendon and I remained, but Bronwyn and Berrima got off and Peter got on. We also jiggled in two jerrycans of fuel, and then fetched a couple more from the nearby service station.

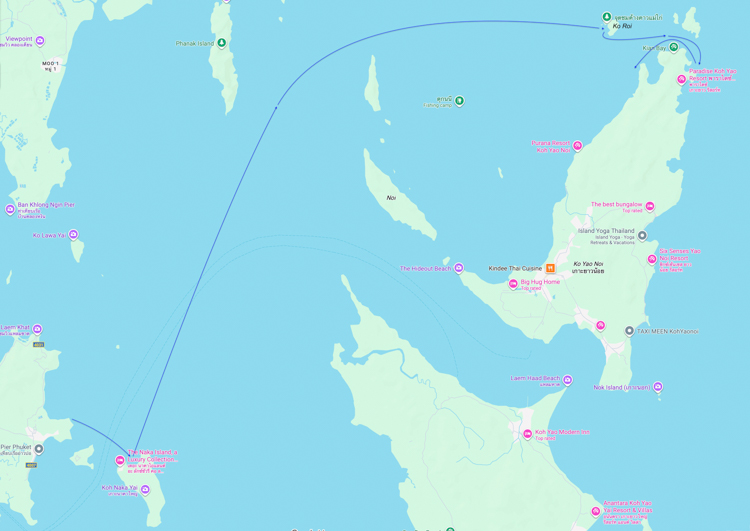

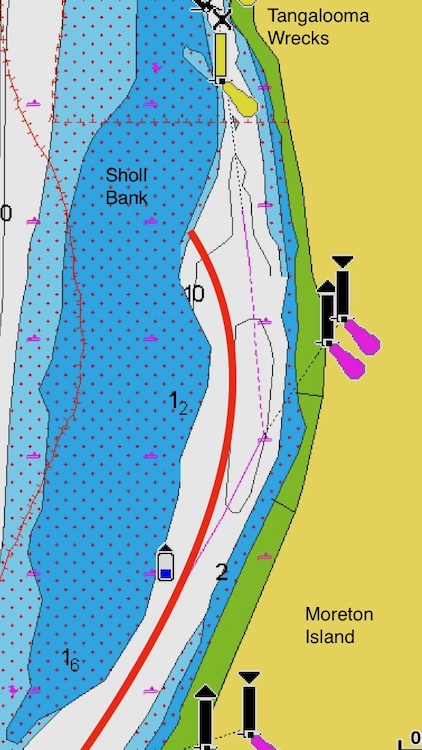

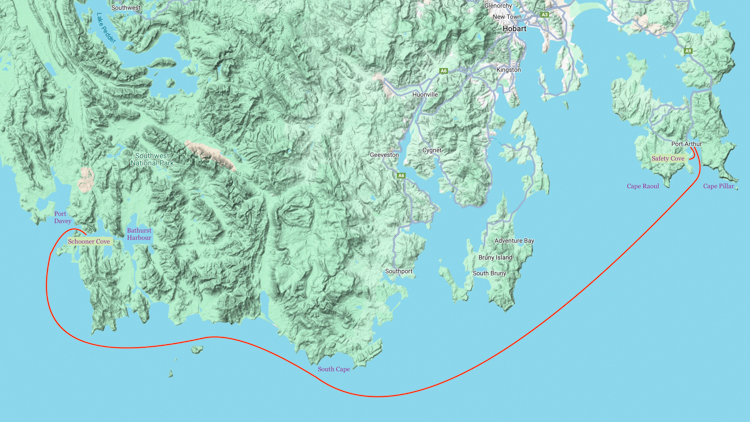

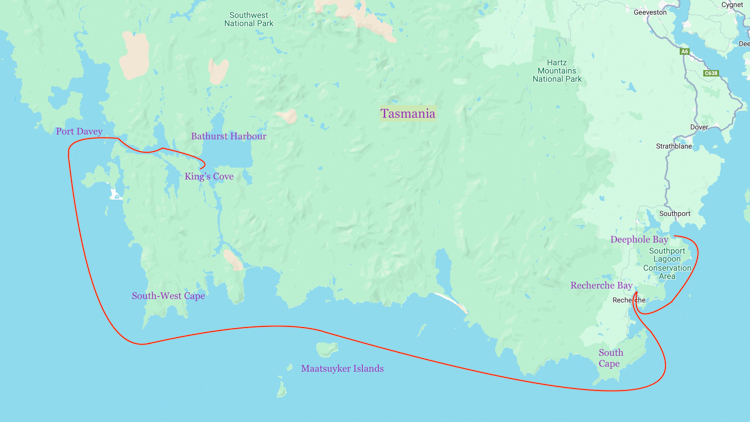

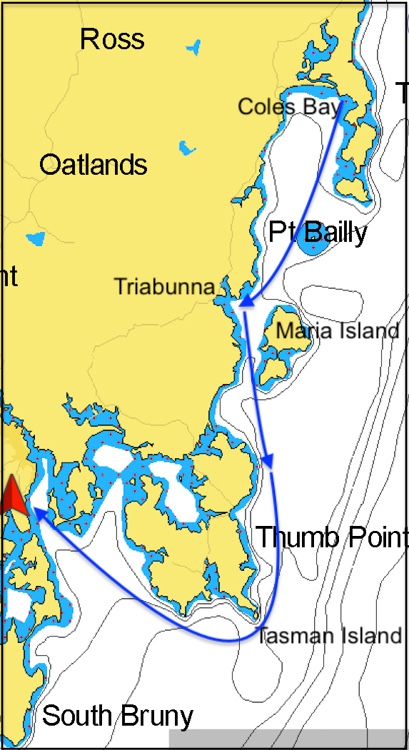

We were preparing the boat for the final 24 hour leg south along the East coast of Tasmania, around Tasman Island, and north up the d’Entrecasteaux and Derwent to Hobart.

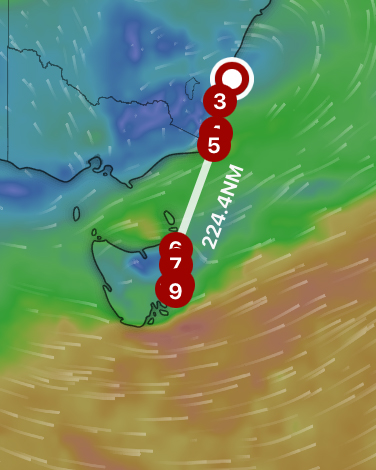

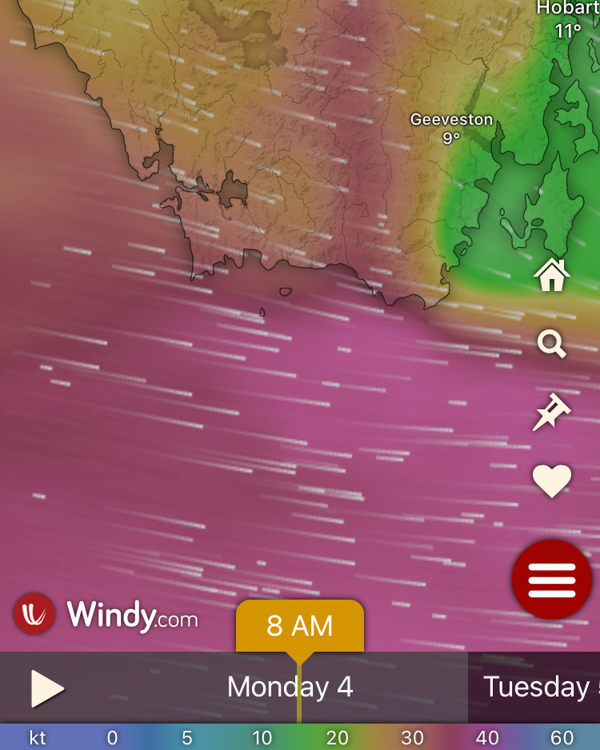

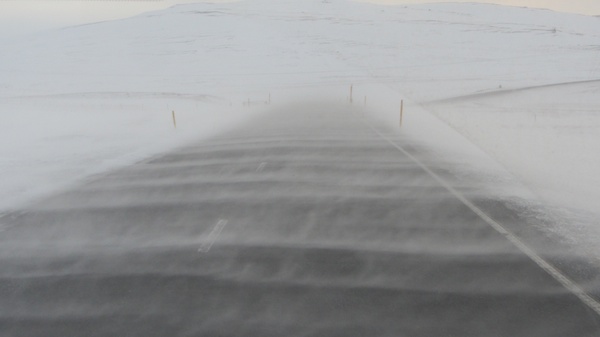

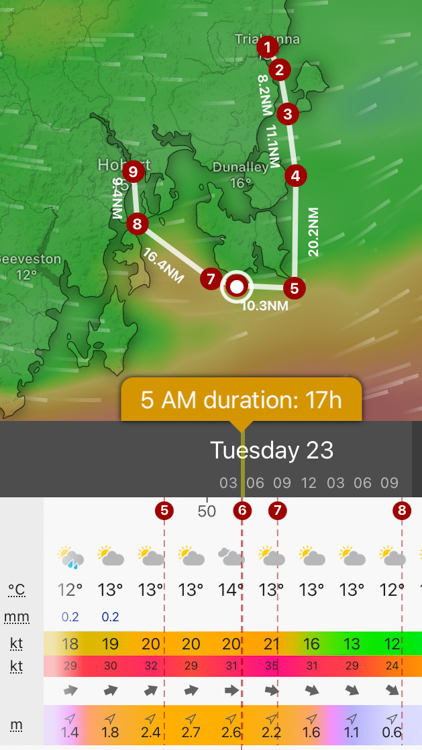

We were expecting bad weather around Tasman Island, where we transition from the Tasman Sea to the Southern Ocean proper. The forecasting models were showing big storms coming up out of the south, but were not too precise about how close they would get before they span off toward New Zealand. In any case, this was our one shot at getting round the island before a major weather system settled in for the final week of the year, so we made ready for sea.

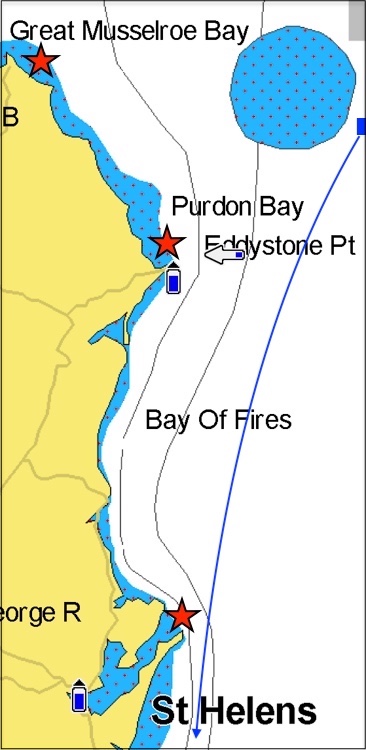

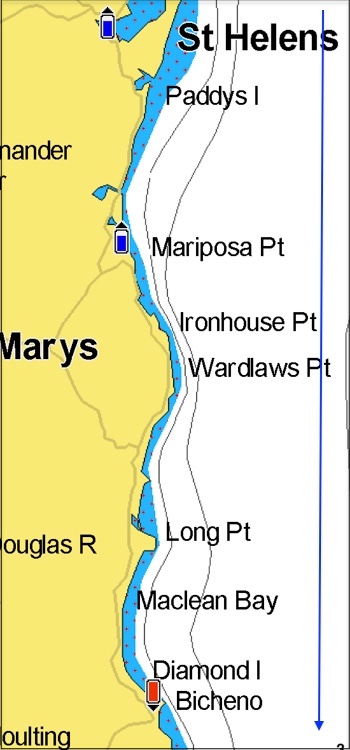

Casting off at a little after 13:00, we hoisted the main and staysail and headed south, making over 7 knots. The sailing was beautiful, but a weather check at 16:30 showed that although the window around Tasman Island would close for us if we kept up our current trajectory, it would open again briefly if we tried again a day later. We chose to sail another three hours down the coast to Triabunna, and then stop and sleep for the night to let the weather pass us by.

We sailed into Triabunna in the last of the daylight, accompanied by a pair of humpback whales, picked up a mooring and made dinner.

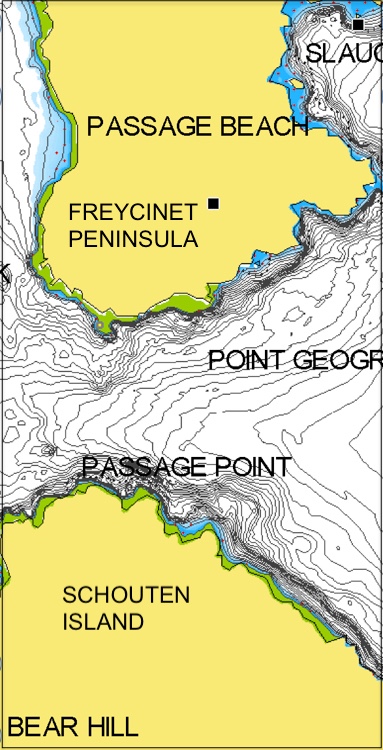

We could see that the conditions around Tasman Island would ease over time before getting worse again, so after a comfortable night and a planned late lie-in, we set off at lunchtime with a 14 knot westerly gusting 20. The gusts increased to 30 knots as we passed Maria Island, fully reefed and still doing 7 knots.

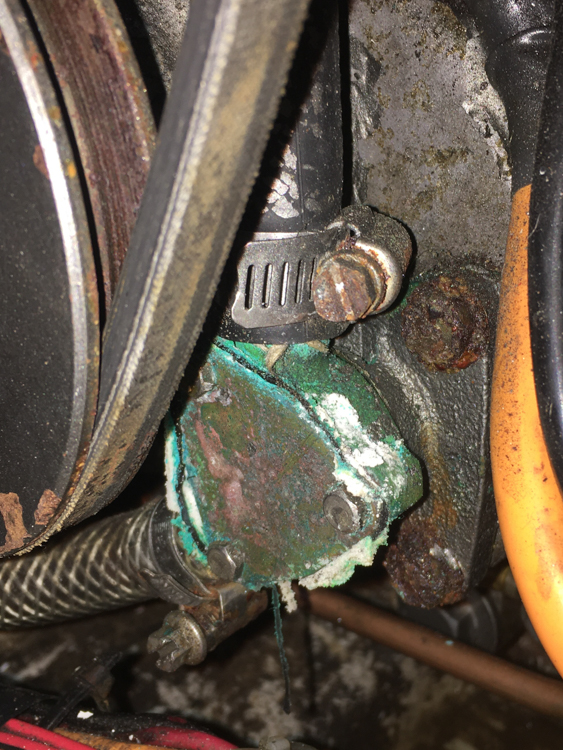

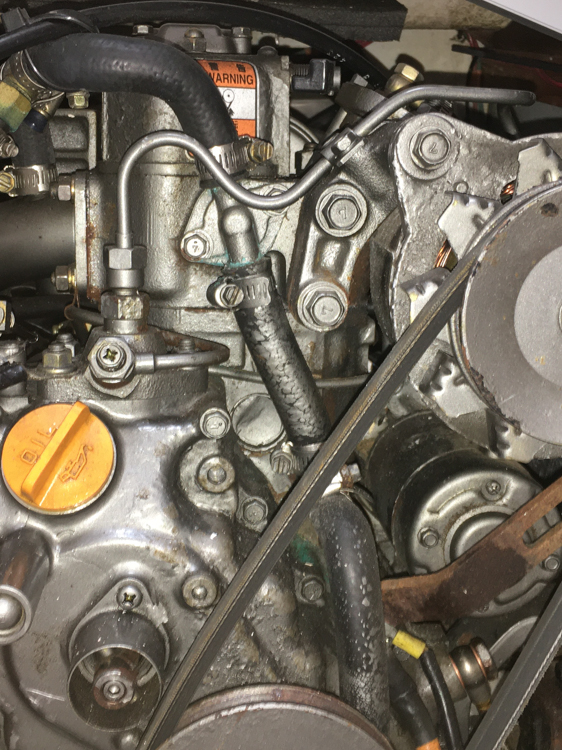

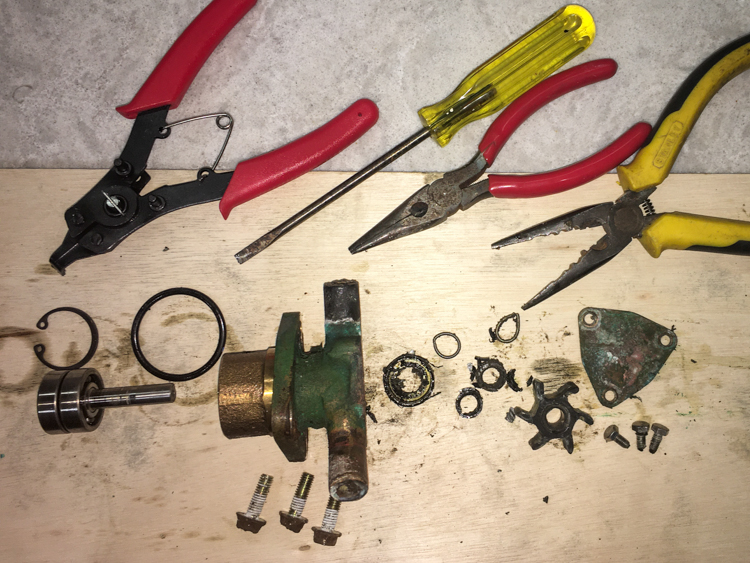

Bearing in mind that Vestlandskyss is a new boat to us, there are still some mysteries in the way that she is set up. I had had my suspicions for some time that all was not right with our Selden Rodkicker, which is a boxed gas strut whose job it is to keep the boom lifted. Tacking the reefed main in 30+ knots, it failed completely, dropping the boom hard onto the stainless steel of the bimini frame.

We needed to get that boom back up before it broke something, and with a bit of fiddling we rigged a topping lift tied around the end of the boom and got it all going again before we had passed Maria Island.

I have mentioned elsewhere in this thread, that I am not happy with our enormous furling genoa. The fabric is so heavy that it flogs in light winds, and when the wind gets up the sail area is so huge that it is almost always overpowered, regardless of whether we are using any of the three indexed reefing points. In practical terms, it works beautifully between 11 knots and 14 knots of wind, and is markedly unhelpful in any other conditions.

Because of this, we generally use the cutter staysail on the inner forestay, which is nice and stable and works under almost any conditions, leaving the genoa safely furled. Nevertheless, I stubbornly keep trying to learn how to use it.

Although for the most part we were comfortably sailing at 7 knots in a 17-30 knot westerly, occasionally the wind dropped into the ‘genoa zone’ and I unfurled it to make a little more speed. On each occasion, it worked just fine until the wind speed increased, at which point it became very hard to furl it back in again, even when pointed into the wind in irons, or turned away from the wind with the furler in the shadow of the main.

It became a bit of a joke. As we struggled once again to clear a too-tight wrap and re-furl, the crew suggested that maybe we shouldn’t try the genoa again in these conditions, and promised to slap me if I unfurled it again.

A few hours later, as we passed the Hippolyte Rocks, the wind dropped once more. We shook out all the reefs and, when Brendon and Pete weren’t looking, I quietly unfurled the genoa, determined to try again.

Vestlandskyss quickly got back up to speed, racing toward the heavy clouds low on the Southern Ocean ahead. All was fine until the southerly change came through, a complete wind reversal in just a few seconds, and Vestlandskyss was instantly laid over on her side in the water. She was fine, still balanced and blistering along at over 6 knots with the port rails in the water, but from the human perspective the deck was vertical as we braced ourselves across the cockpit, the sea whizzing past beneath our toes.

We put the genoa away, reefed, and reefed once more. I promised not to touch the furler for the rest of the trip. The crew promised to slap me harder, if I did. The wind continued to rise, and we reefed again.

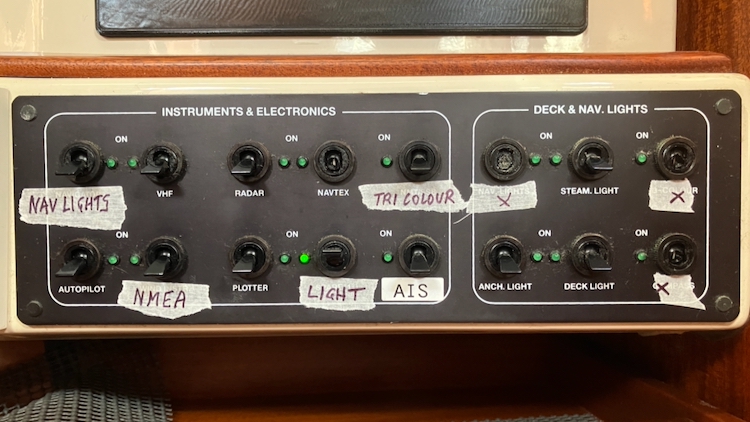

By eight o’clock in the evening, in the last light of the day, we spied Tasman Island and it was clear that there was rain falling either on or just beyond it. This was the weather event that we had been expecting. I switched on the radar to keep an eye on it as we approached through quiet seas.

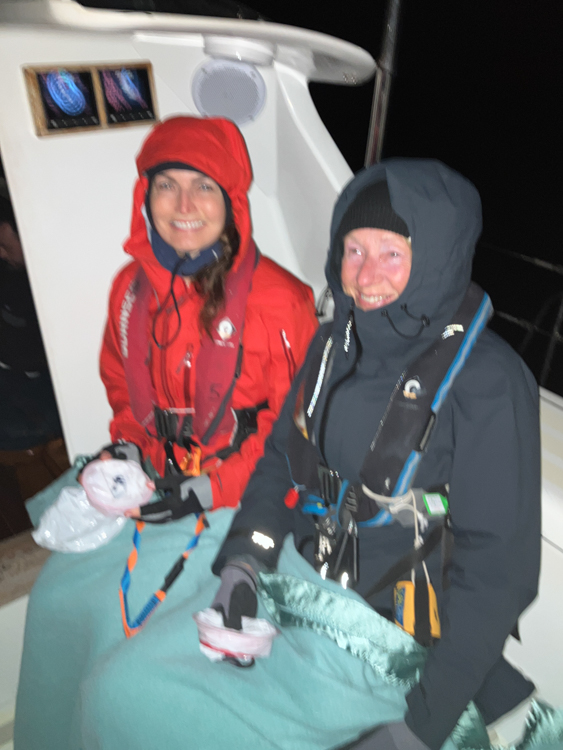

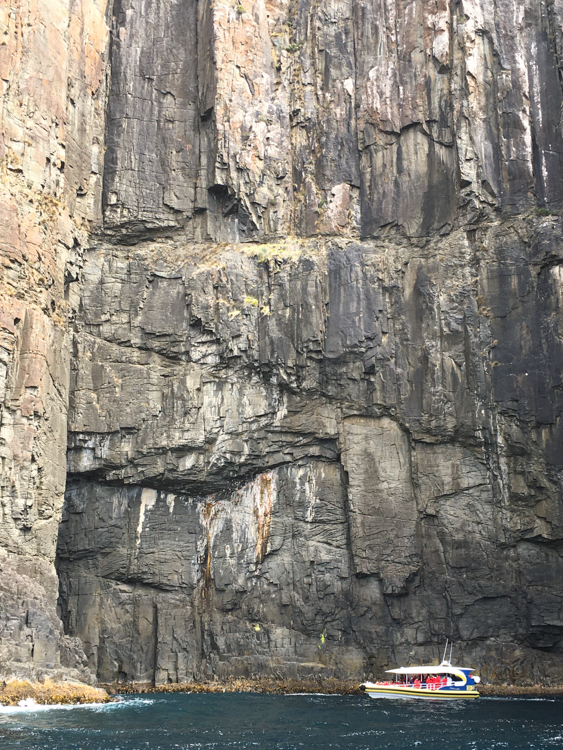

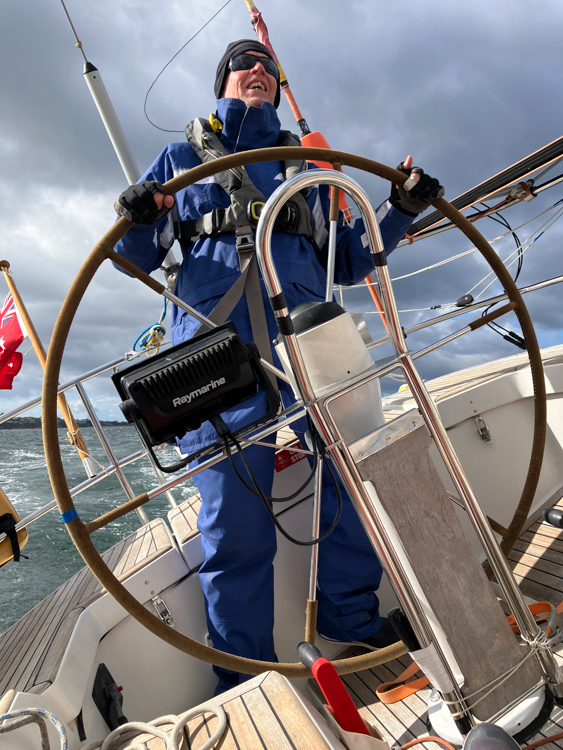

As we came level with the island, we entered a wall of rain. The swell increased to several metres, and the waves began breaking as the wind climbed to the high twenties and higher. It was quite gnarly for a bit, but Vestlandskyss easily shrugged it off and ploughed through it until we got far enough out into the ocean to tack back around the island, very close-hauled and just sneaking past under the gloom of The Monkeys in the dark.

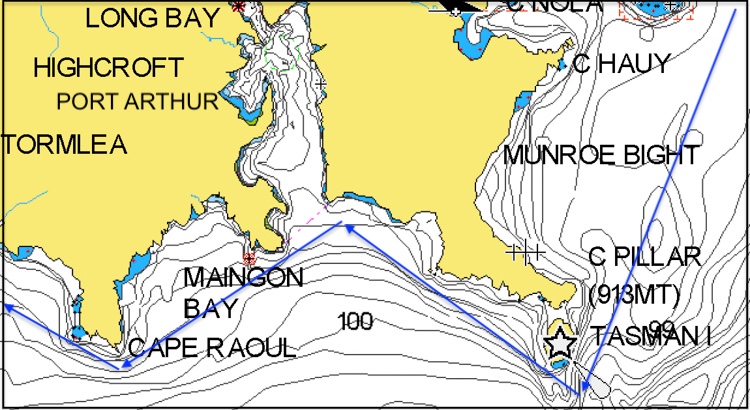

The yacht was behaving beautifully. Other boats that we have known would have been launching off the tops of the waves, crashing into the dips, wallowing in the cross-swells. The Sweden 390 just calmly sailed her way forward into the howling gusting wind, knifing through the waves and then shrugging the excess water off the decks. Nevertheless, I chose to skip my berth time and stayed on deck, steering by hand under the cliffs and up into Maingon Bay. We had an option, here, of nipping up to Port Arthur for shelter, but the weather window was closing for good and we’d end up trapped there for days, so we tacked back out to pass close under Cape Raoul. I passed over the watch to Brendon and Peter, and went below to get dried off and warmed up.

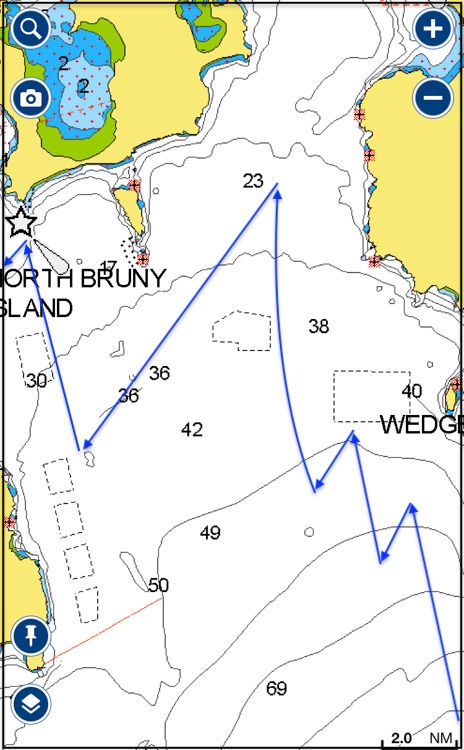

By the early hours of the morning, the storm had moved eastward across the Tasman. What wind there was left to us, was directly on the nose, so we motor-sailed the final stretch to take us around the corner into the d’Entrecasteaux Channel. When I awoke, it was still full dark, but we were tacking westward toward South Bruny Island. We were tantalisingly close to home. Brendon and Peter went below to rest.

The next part is comically embarrassing. Alone in the dark, I pointed the nose northward, turned off the engine, hoisted all sail (declining the temptation to unfurl the genoa), and soon had us creaming along at 7 knots. Brendon felt the difference in motion, stuck his head into the cockpit, raised his eyebrows at the speed, and went back to bed.

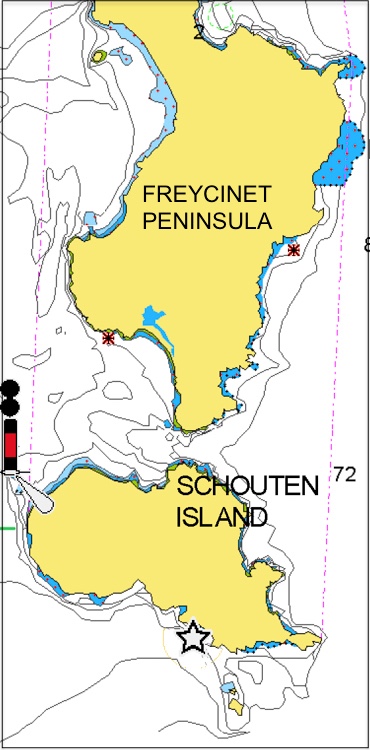

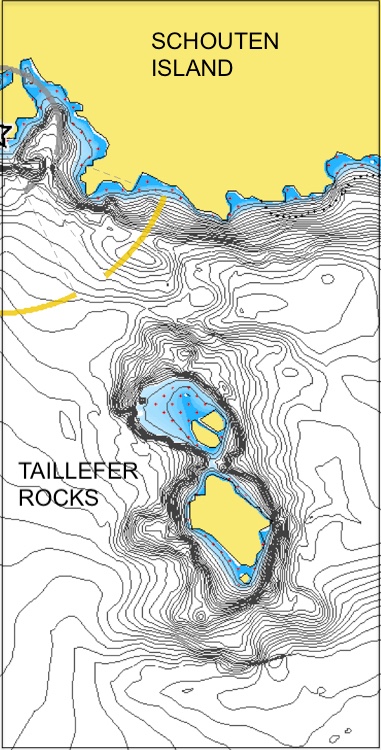

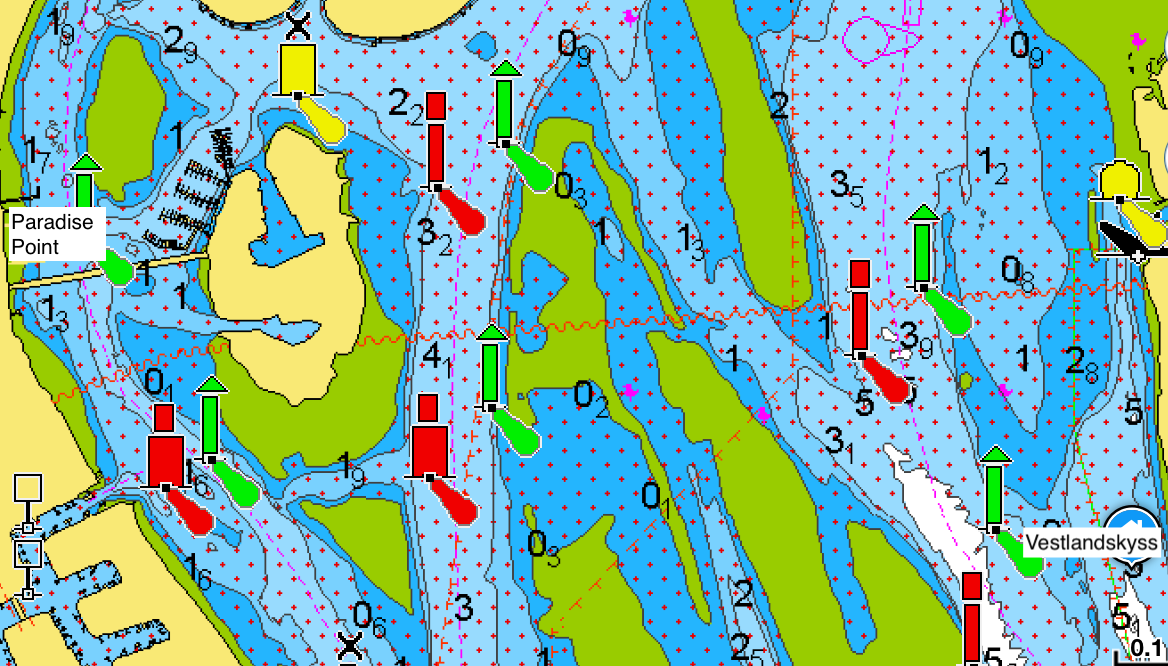

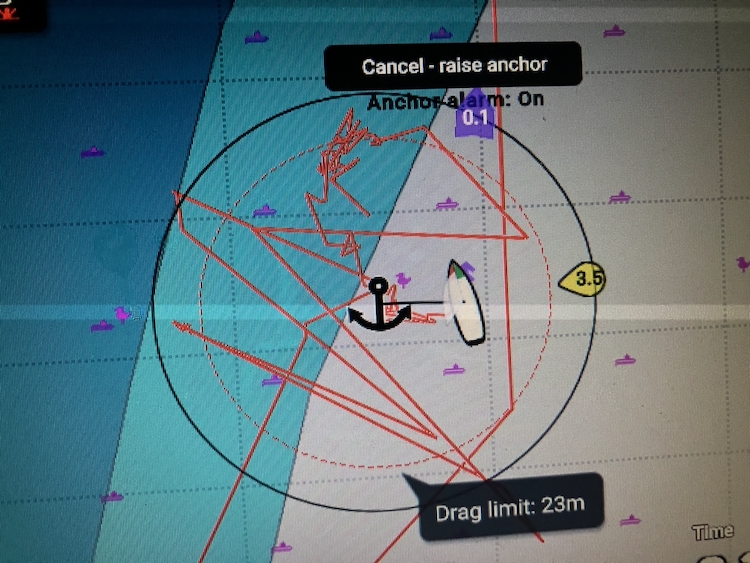

I was still tired. Clearly marked on the chart were a number of zones with no markings, which I took to be the boundaries of fish or oyster farms. Racing towards the first one, I could discern no beacons or markers in the pitch black, particularly amongst the confusion of lights ashore. There was plenty of wind, so I chose to tack around them.

We don’t have any lee cloths fitted below (note to self: add that to the list), so every time I tacked, the guys tumbled out of their bunks and had to move to another one. Blithely unaware, I tacked and tacked again to get around these mysterious charted objects.

Eventually the crew got tired of being rolled around and came on deck. The sun came up, and it soon became clear that the marks on the chart simply delineated anchoring areas for commercial ships; there was nothing physical there at all. I could have sailed right through them. How we laughed.

A couple of tacks to clear the Iron Pot and Blinking Billy, and the Derwent Sailing Squadron hove into sight.

The wind vanished, we dropped the sails, and Peter made coffee. Under motor on glassy seas, we burbled gently into the dock, after a total passage of eleven days, and our families caught the lines. We were home.