It is relatively easy to fly into the International Airport at Nuku’alofa on the southern Tongan island of Tongatapu. However, since the country of Tonga comprises some 171 islands spread out over 700,000 square kilometres of the Pacific, the chances are that when you arrive, your onward journey will probably be a bit more than a short taxi ride. In our case, we wanted to get to one of the northern islands, Vava’u, and I had been delighted to discover that Royal Tongan Airlines flies an old DC3 Dakota on that route. For reasons that remain obscure, but which are possibly the result of too many childhood Biggles books, I have always wanted to fly in one of these, so we’d arranged tickets.

The DC3 was in fact standing at the airport, but we were led over to another bakelite-era twin-prop of uncertain vintage. The pilot told me that, of the three duplicate flight systems aboard the DC3, usually only the backup and emergency were working, and since the backup had now given up the ghost, he was refusing to fly her.

The Dakota waits forlornly for repairs

We were picked up by Dave the taxi driver, a smiling Tongan with interesting teeth, who decanted us into a small boat which putt-putted us across to Mala Island, our home for the next few days.

The boat was piloted by the smiling and eminently capable figure of Henry, who turned out to be General Manager, bartender extraordinaire, and Mr Fixit for the somewhat curious world that we were about to enter. The owner, also called Dave, a rather manic expat Californian, had recently refurbished the small island with the intention of making it a haven and recording studio for visiting rock stars. Be that as it may, he had an enormous stock of name-dropping stories and, apparently, a record label. He was also proud of the consternation that he had caused in the local area by employing a Tongan manager, and paying both him and the rest of the staff “a fair wage”.

Dave gave the impression of being something of a one-man tornado in local Vava’u politics, making himself popular by inviting Tongans to enjoy the facilities, but on the other hand, the Tongans he mentioned tended to be well placed in the royal family and in the police force.

As we were to discover, scratching backs is a way of life here. The deal on Mala Island is that you pay 45 Tongan dollars a day, and then eat whatever you want. On the one hand, this limits you to whatever happens to be in the kitchen; on the other, the food is prepared by Todd, an excellent chef who Dave apparently pinched from some US restaurant.

On arrival, though, we were too exhausted to think, let alone deal with crazy Americans, so we stumbled up the jungle path to our little cabin and into bed, scarcely even noticing then that it was beautifully decorated with traditional Tongan woven leaves and hand-painted papyrus.

Sunset from Mala Island

When we awoke, we had coffee, we had lunch, and then dozed off again.

Bronwyn demonstrates Royal Tongan Coffee in our traditionally decorated island cabin

Eventually I got up and strolled around the perimeter of the island, an exercise that took less than an hour and involved stepping over a lot of coconuts.

Coconut seedling

That evening in the central bar area, the beers began to flow, poured by the incomparable Henry. He told us the story about how at age 12 he had left school because he wanted to be a taxi driver. He cleaned and washed and gardened at his uncle’s house until his uncle taught him to drive. That same uncle then spoke to the chief of police and got special permission for Henry to have a taxi licence, even though he was far too young. Many years later, having learnt English and how to deal with tourists, he picked up Dave from the airport, ran a few errands for him, and then got offered the job of General Manager. That, we gathered, was Tonga in a nutshell.

Island time began to kick in.

We dived on some wrecks.

A wreck in Vava’u harbour

Giant clam staking a salvage claim

We snorkelled on the reef, and in some underwater caves.

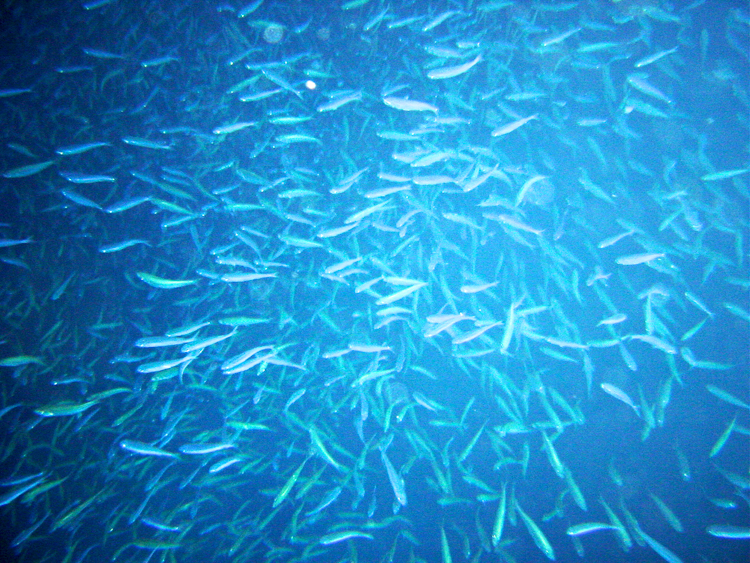

A shot in the dark

This cave is full of fish!

After a while we just had a load of spare scuba tanks delivered to the island, and went diving from our room. All around the island were coral-heads several metres across, each a blaze of colourful life, and each apparently the nursery for one or another species of coral fish.

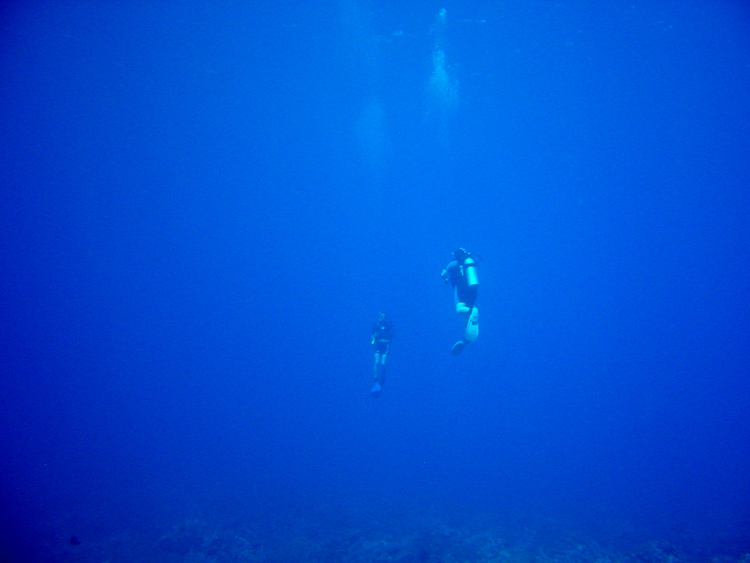

Divers tend make a lot of fuss about the visibility, or “viz”, the distance that you can see underwater on a particular day or at a particular location. This has never made much sense to me, because you spend most of the time looking at things that are right in front of your nose, so I ignored it when they started to go on about sixty metres of vis. Who wants to see things that are sixty metres away?

I changed my mind on a Tongan night dive. Usually at night you only go down a few metres, and stay within hand contact with your buddy, because it is very, very easy to get disoriented and lost. Not so in Vava’u. The moon shone down to twenty metres almost like daylight, and Bronwyn and I could not only see each other five metres apart, but could even recognise one another amongst the other divers.

The Readings out in the deep blue

And, of course, we met lots of colourful characters while drinking cocktails in the bar.

The floor-show beats flaming Sambucas any day