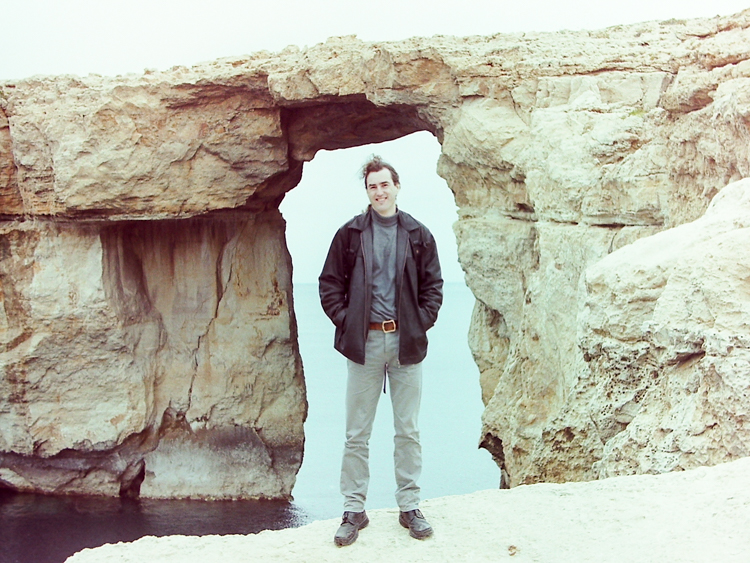

Framed by the Azure Window

The Maltese speciality food is rabbit, which you can buy roasted, stewed, or made up into a spaghetti sauce. After a few days on the island, you realise that this is because the terrain does not lend itself to the existence of any larger animals, or indeed to any kind of farming at all.

Dingli Cliffs: as high as the topography gets

The landscape is uniformly scattered with white head-sized boulders, offering little cover to anything apart from rabbits and small birds. The former are, evidently, eaten. The latter are the subject of the national sport of shooting at them, the smaller the better. Every fifty metres or so of the rubble-strewn landscape is equipped with dry-stone hides providing protection from the sun and a good view of a selection of artificial wire and wood perches designed to tempt the little finches and tits above ground level.

Any doubts of the ubiquity of the lunar landscape are easily dispelled. Climb to the top of the nearest convenient hillock and you see the whole island spread before you, a flat dish centred on the enormous dome of Mosta cathedral. Any visitor quickly realises that most of the Maltese maps and signposts are incorrect, wishful or just plain imaginary, and we soon discovered that the easiest way to navigate was to drive to the top of the nearest rise, spot the Mosta Dome, and take it from there.

Mosta Dome. If you can see it, then you’re not lost

In fact, driving anywhere on Malta is an interesting experience. Although the roads are technically tarmac, much time and a lot of traffic has passed since they was originally laid, and in the intervening years they have simply been patched over and over again, until now there are very few places where the original road surface can still be seen. There are holes and craters everywhere; while we were there, a crack opened up in the middle of the main road outside our hotel which was fully a metre long, half a metre wide, and of cavernous depth. It yawned, unheralded, for most of our stay, after which a half-hearted attempt was made to fill it up with tarmac, reducing its depth to a mere foot or so below the road level.

Mix all this with Italian-style foot-to-the-floor style of driving, a propensity for fast cars, and a complete disregard for other vehicles’ bodywork, and driving becomes an exhilarating experience. This is not to say that the Maltese are bad drivers; on the whole they seem to be highly skilled (possibly there is some Darwinism at work here) and they are polite and courteous on the road… until you show signs of hesitation or weakness, at which point they move in for the kill. It was for this reason that we were not overly distressed when our original hire car, an elderly Escort, was stolen on the first night, because the replacement Hyundai had much more power and responsive handling and allowed us to level the playing field a little.

Two strong themes persisted during our stay, and coloured everything that we saw. The first is a very long and strong sense of history. Malta is home to the oldest structures in the world, pre-dating the pyramids and Stonehenge.

The ancient temple of Hagar Quim

Millennia later, much of its modern history was dominated by the Knights Templar, who pretty much owned the place for hundreds of years, and who built forts and castles against what they saw as heathen Moorish pirates.

The gate of the walled city of Mdina

The church in Gharb

Messing around on the salt pans by Bugibba

However, the Moorish influence is clear in the Maltese language, which is clearly of Arabic origin although – uniquely – written using the Latin alphabet. More recent history includes Malta’s legendary stand in the last World War, and its current status as a freeport and financial centre.

The second striking thing about Malta is the intense pride that the locals have in, well, everything. This is particularly evident in Valetta’s small but excellent War Museum, where tales and pictures of the good natured stoicism of the civilian population under siege invite comparison with blitzkrieg London. Drawing such a comparison is probably not all that surprising, as Malta is intensely British. Although it gained independence in 1976, the whole population is bilingual in Maltese and English, and (apart from the Arabic street names) a glance up any shopping street could easily fool you that you were in some English town.

A fleet of ancient but lovingly restored English motor coaches, long retired from active service elsewhere in the world, form the local bus service. Each resplendent in yellow and orange livery, with the exact make and model proudly displayed in sprawling calligraphy where in earlier times you might expect to see a destination plate, these owner-operated dinosaurs provide a noisy, uncomfortable and unreliable service over the potholed roads. Apparently immune from even the few observed road laws, they appear to have a special dispensation to operate without lights, which can be somewhat alarming late at night.

Some examples of the astounding Maltese bus fleet

While driving, walking, or simply standing still on any convenient hillock, you cannot help but notice that there seem to be rather a lot of churches. Maltese churches tend to excess. Every small town raises money to support its own church by local subscription, resulting in a certain amount of one-upmanship between neighbouring communities. Many local churches thus more closely resemble mainland cathedrals than places of daily worship, the whole process culminating in the enormous structure on the neighbouring island of Gozo, apparently built in direct competition to the Mosta dome.

The tiny local village church in Xewkija

Notice how it huddles insignificantly

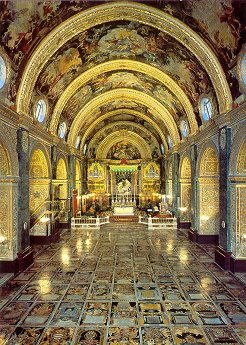

It can be surprisingly difficult to get into these churches, as they keep short and irregular opening hours, but it is often worthwhile. In many of them, the walls are covered from floor to ceiling with red tapestry, and the floors are made entirely from colourful marble tombstones.

St Johns CoCathedral, Valetta. Actually this is a postcard

This small country is a gem. We spent days wandering the byways of the ancient towns, discovering tiny restaurants that turned out to be amazing gourmet experiences. There are fascinating corners such as the little museum of ancient working life in Gharb, and the bone-filled catacombs of Rabat. And don’t get me started on the excellent local wines…