The hail storm eased off, leaving a thick white layer of marbles that crunched into powder between the fat tyres and the cobblestones. It was early on Boxing day morning, and as I carefully eased my motorcycle over the slippery surface, cosy lights glimmered from the snug breakfast warmth of the Yorkshire cottages.

My pillion, Iain, and I were heading for the North Yorkshire moors. Once we got there, we intended to spend the few days between Christmas and the New Year crossing England from east to west in time for our annual New Years booze-up in the Lake District. We were, of course, fully aware that the Pennine passes are usually closed at that time of year, but if you’re trying to find adventure in your own country you may as well make it interesting.

Sutton Bank

The temperature dropped steadily as we approached the loom of Sutton Bank, westernmost outpost of the Hambletons, a range of hills between us and our chosen starting point of Whitby. A sudden squall of snow obliterated my vision, forming a thick veneer of ice on my helmet. Unable to open my visor for fear of getting snow on my glasses, I had to be content with riding one-handed while continuously scrubbing with my left hand. It was already cold enough for the snow to settle even on the wet road, and a succession of sharp bends between high hedgerows began to make life slightly interesting.

We made it as far as the base of Sutton Bank before I decided that not all of the frantically flashing and hooting oncoming car drivers could be delinquent hooligans, so I pulled over into a convenient snowdrift to take stock.

Under Wass Bank, in the snow

It was clearly snowing up on the Bank, but the clouds parted occasionally to reveal that something else was also going on up there. Short jigsaw visions of frantically flashing brake and hazard lights added up to the realisation that cars were getting about halfway up the Bank and then slowly sliding down backwards until they could get enough purchase to turn round and come back down.

We consulted the map, and pointed the Honda Revere back at the village. The new heading was a wide sweep around the southern flank of the Hambletons, and above us the weak midday sun picked metallic highlights from the dark cloud that had now settled permanently over Sutton Bank and its luckless motorists.

Wass Bank

We turned east under Wass Bank, and considered our options. We could either continue our sensible lowland detour, which would not take us far out of our way and which would avoid the Hambletons altogether, or we could chance the louring bulk of Wass Bank.

The gradient was fairly fierce, but clear of snow until the final thirty feet, where it became a steep ramp coated with a couple of inches of fresh powder. We rolled to a halt just below the snowline and squinted into the glare. Traffic signs indicated that there was a crossroads on the brow, but the thick woods on either side obscured our view of oncoming traffic.

I left Iain by the roadside and took a run-up, only at the last second deciding to stop at the top instead of barrelling blindly across the crossroads. Fighting to keep the steeply inclined machine level with the Give Way sign, my heart skipped as two Volvos scrunched past. Had I been alone I would have had to stay there until the snow melted. Fortunately, Iain was wearing hiking boots, and so once he had struggled up the slope himself, he was able to get enough traction to give me some sort of a push. Half way across the junction, the back wheel attempted to overtake the front, and I put my own foot down to steady the bike. Unfortunately, I was wearing flat-soled motorcycle boots, and on that slippery surface I may as well not have bothered.

With a nasty crunching sound, the Revere toppled over in the snow. Cursing the vagaries of the manufacturers of motorcycle clothing, we righted the now slightly battered bike and surveyed the damage. The hard plastic of the right hand pannier had cracked like an eggshell and a piece about four inches long was missing, but the box had maintained its integrity and nothing seemed to have fallen out. Iain went back to try and locate a white piece of plastic in the white snow, while I stood by the equally white bike trying to pretend to motorists that it was bright red and bore absolutely no resemblance to the snowbank against which it stood.

A couple of miles down the road was the town of Helmsley, so we stopped to buy some food cans, a can opener (my fifteenth, I think. Where do they all go?) and a black plastic bin liner to wrap around the pannier and stop our luggage from getting too wet, just in case it started to snow again.

And snow it did. As we rode down out of the hills and headed northward across the flat exposed moorland toward Whitby, a storm came up out of the west and threw everything it had. I had to lean the bike right over into the gale, virtually scraping the footpegs just to travel the dead straight road over Goathland Moor. The snow drove horizontally across the darkening landscape, my hands were going numb even protected by two pairs of gloves, and I was back to continually wiping my visor in order to snatch brief glimpses of the road. One day, I swore, I would buy a set of heated handlebar grips.

Strange Happenings in Whitby

Then as dusk finally fell, we entered Whitby, and the snow stopped. The town was, not surprisingly, deserted. We parked up in the shelter of some public toilets by a children’s paddling pool, and considered our next move. This was obviously just a lull in a storm that looked set to blow all night, so for the first time that day we used the logic that raises us above the apes. To shelter from a westerly storm, we reasoned, camp in the lee of an east-facing cliff.

Whitby sits on the east coast, separated from the sea by a vertical drop of some hundred feet or so, with a small tarmac footpath winding in a series of hairpins down to the beach. The path is exactly the same width as a fully laden Revere. We parked about a third of the way down, and erected the tent a few yards away vertically upwards on a convenient flat grassy shelf.

Soon, some hot food and cold beer later, we drifted off to sleep.

Nobody knew where we were, apart from a vague “on the bike north of Coventry”, and we certainly hadn’t planned to camp above the beach at Whitby; it had just turned out that way. So for me to be woken up a few hours later by someone standing outside my tent calling my name was utterly ridiculous. In bewilderment I poked my head out, to meet the eyes of an embarrassed policeman looking most uncomfortable balanced on the edge of a cliff in a thunderstorm.

Mr.Reading?, he said. I tried my best to act cool. “Is there a problem, officer? No sir. Or at least, there wasn’t, but I think we’ve caused you one…”

Apparently, someone out for a midnight stroll down the beach in the rain had seen the white Honda perched on the path, and had reported it to the police. A constable was sent down, took the registration, failed to notice my camouflaged tent in the darkness, and rang Fenella in the small wee hours. “We don’t want to bother you, they’d said, but w’eve just found your boyfriend’s bike halfway down a cliff…”

After the hysterics had passed, they admitted that it was in fact parked and locked rather than crumpled and smouldering, and, with her teeth firmly clenched around a brandy bottle, she ordered them back to look for the tent, and then ring her back, or else.

Not crashed or burned

The rest of the night was uneventful, and next morning we got up with the dawn (not as early as it sounds in late December), road into town and wandered up to the Abbey. The cold soon drove us back down, and a different policeman directed us toward a cafe and a fried breakfast, and after a suitable amount of huddling against a radiator we set off westwards over the North Yorkshire Moors.

Across the Moors

We had decided to take the plethora of minor roads that accompany the railway on its journey toward Middlesborough, and had chosen two potential routes, one that wandered out over the high moors, and another that stayed safely in the valley with the trains. We planned to go high in good weather, and stay low in bad, and there was plenty of scope for switching between the two as circumstances altered.

The morning was glorious, the roads dry and the bends evil: in short, perfect riding conditions. We admired the scenery around Egton, and paused at Glaisdale where road, rail and water routes cross in a picturesque crosshatching of bridges. We were just about to take our high road when the rain started up, so amazingly we took the sensible option and made our way down through the mass of roads around Castleton, pausing briefly at a vandalised sign before continuing westwards.

Almost immediately I was presented with a torrential ford crossing. Iain got off, and I tentatively selected low gear and eased gently out into the torrent. The water came over the hubs but I was delighted to find that the bike showed no tendency to float like a car, but just ploughed along the bottom and up the other side. Rather than stop on the immensely steep valley side I ran up to the top and waited for Iain, who had crossed over the footbridge.

The hill should have made me think, but I was extremely chuffed about the ford and the weather was clearing again. Five minutes later we were riding blind through a cloud under a deluge of icy water. Visibility was down to a few yards and the road was littered with soggy sheep. We werent as miserable as the sheep, for we knew from our map that we had only to cross this small ridge of high ground before the descent into Kildale. But the ridge went on, and on, and on, until we fetched up against a road junction that just had no right to be there.

There was a road sign, but it was unlit and we had to get off and trace the letters with our frozen fingers, and then huddle over the dull yellow glow of a headlamp that I was sure used to be a fiercely burning halogen. There was nothing wrong with the electrics, just a thick coating of ice particles that no amount of rubbing would shift. That page in my Ordnance Survey atlas is now warped beyond recognition, but we found out where we were, neatly sandwiched between two symbols that mean ‘viewpoint’, balanced right on the highest point of the moor.

It was time, once more, to turn around. I successfully negotiated the sodden sheep and then, out of the cloud and full of new-found confidence, burned down the hill toward the ford, braking at the last minute and contemptuously hitting it at about 20mph. At the other side I stopped and thoughtfully emptied the water out of my boots.

Once off the moors we stopped at a village called Stokesley for a pub lunch and to dry my socks. They had good beer, good food, and lots of drinkers who watched in polite amazement as we peeled off layers of damp clothing and stacked them in front of the fire. Inevitably, there was the man who used to ride a Vincent, and he reckoned that the A66 through the Pennines was now open. We lingered as long as we could, but we wanted to camp somewhere closer to the pass to give us time to get over as early as possible the next morning. We donned our gear and went back out into the rain.

Richmond

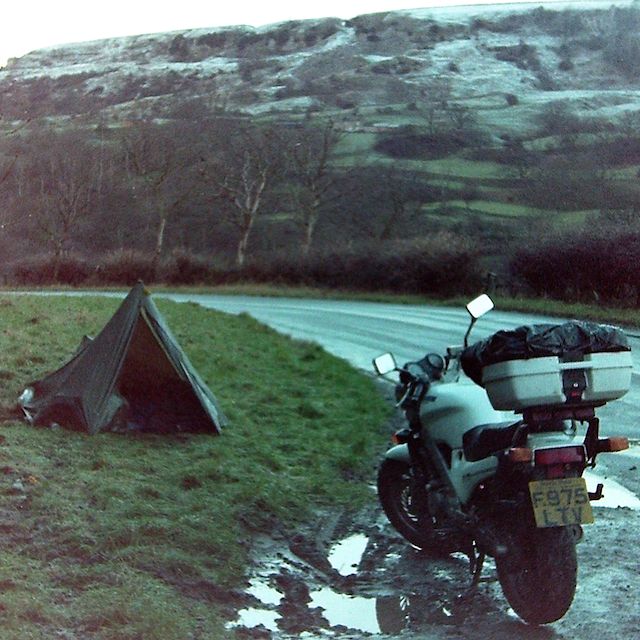

Richmond, situated in the lowlands to the east of the Pennine passes, fitted the bill perfectly. All that remained was to find a place to sleep, and a few minutes drive soon revealed a wide grassy verge next to a quiet lay-by.

The next morning was unbelievably cold. The alloy of the tent-pegs was cold enough to burn, but we couldn’t grasp them through our gloves, so we ended up leaving the bike engine idling, pulling the pegs out barehanded, and returning to the bike every few minutes to jam our frozen fingers up the exhaust pipe. The stuff all fitted back in, but as I was locking the last pannier the key snapped off in the lock. It was that cold.

Cold Camp

A welcome hot breakfast in Richmond, and some more radiator-huddling, saw us setting off on foot to explore the town. There was a lot to see, but we spent most time at the castle around which Richmond is built. The restored tower commands tremendous views, and the lady who sold us our tickets used to be a biker herself, and allowed us to bring the bike up from its two-hour parking zone and leave it in the castle grounds. Below the ruin is a wide brown river that tumbles over a small cataract of falls. I commented on its suitability for kayaking, and the local standing next to me responded, “Oh yes, its very popular. We lose one or two canoeists a year!”

Through the Pennine pass

And then we were off once more on a swift blast toward the Pennines and the infamous A66. The pass was, in fact, open, but the dales were deeply buried in snow and the traffic slowly moved nose to tail in one another’s tyre tracks. We passed the hotel where, until very recently, a group of guests and motorists had been trapped for a week without food, and then thankfully dropped down the other side to the tea shops of Appleby, and the fast winding run through Windermere and Ambleside to the warm welcome and hot showers of our hotel under the Langdale Pikes. The guest ales were settling in their barrels and the first arrivals were trickling in for the annual celebration of the end of the old year’s tales, and the beginning of the new.