We had been warned about the dragonflies, and here they were, swarms of them coming out of the desert, big fat and very very hard. Every time we stopped, enormous black crows would descend and pluck the mangled and juicy bodies from the motorbike.

We were riding across the Nullarbor Plain, the world’s largest single piece of limestone, comprising about 200,000 square kilometres of desert separating Western Australia from Southern Australia. There is only one road across, and the thousand-kilometre Eyre Highway has become a long-distance traveller’s icon. The story goes that, far from being the aboriginal name that you might expect, the word Nullarbor was coined by early explorers from the schoolboy Latin for ‘no trees’. This is something of a misnomer, because in fact this area forms part of the largest temperate forest in the world. It is a land of stark contrasts; red earth, bright green low-lying shrubs, and impressive glossy red gum trees, all stretching out forever beneath a vivid blue sky.

The logistics of living in such an arid environment preclude any kind of town on the Plain itself. There are a few hardy cattle stations out there, but along the road civilisation is represented by roadhouses strung out at intervals of 200 kilometres. Largely owned and operated by the major oil companies, they provide fuel for traffic and road trains and offer varying degrees of accommodation, food and camping.

Some are prosperous and well-appointed, others run down and a little squalid, but since 200 kilometres represents the maximum distance that the XJR 1300 can go on a single tank of fuel, we were obliged to stop at each and every one.

Although it was winter and there was a fresh wind blowing in from the Southern Ocean, there was still an appreciable heat haze on the road. Mirages and inversion layers were common, and it was often quite a few miles before you could figure out what it was that was coming towards you, or even if it was coming towards you at all. The prettiest mirage turned the whole of the road ahead into a perfect reflection of the blue sky overhead, so that it seemed that at any moment you might drop off the edge of the world.

All trailers are restricted by law to 100 km/h, and since just about everything from the road trains down to the smallest car and even some of the motorbikes are towing trailers, this means that the traffic, if you can call it that, moves at that same speed like discrete beads along a wire. Horizon to horizon, you might see one bead up ahead, and possibly one far behind, but that’s as congested as it gets. Going a little faster than this, we would slowly catch and pass each road train, but it was sometimes a long battle through the vortex of turbulence that could extend hundreds of metres behind each rig.

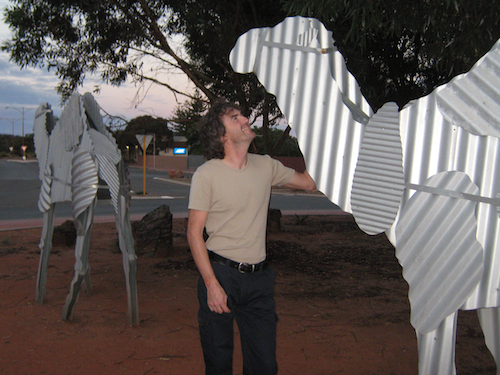

It is a point of pride for every Australian town, municipality or region to claim to be home to the largest, longest or oldest feature of Australia or, preferably, the world. If a particular region lacks any suitable natural features, then the locals will build something. Typical examples are The Big Trout, The Big Merino and The Big Banana. We have personally drunk beers in at least half a dozen Oldest Continually Licensed Premises In Australia.

The Nullarbor boasts not only The Longest Stretch of Straight Road in Australia (146.6 km) but also The Longest Golf Course in the World, which puzzled us a bit at first. All became clear when we realised that there was a tee and a hole at every roadhouse. The whole thing could be said to stretch out over more than 1100 km, but you have to drive for several hours down the highway to get to each tee. Of course there isn’t much in the way of green; the terrain is described as ‘natural ground’.

Along the road, the landscape remained largely flat but the flora changed regularly, presumably reflecting changes in the underlying hydrology. The underbrush remained hummocky and rarely exceeded a couple of feet in height, but the amount of bare earth between the bushes varied, and trees came and went above. In several places we passed entire forests of dead trees where presumably the water table had dropped temporarily out of reach. In most of these, new growth was now springing up from the bases of the trunks, so presumably the aquifer had since recovered.

The lack of water was a constant theme. With only a few inches of rainfall a year, most water is trucked in to the roadhouses at great expense. Showers are available at a price, but unless you rent a cabin you are expected to bring your own washing and drinking water with you.

A couple of days into the Nullarbor, we came across a road train parked in the bush and a hired motor home lying on its side. We stopped to see if we could help, but the road train driver, who had seen the accident and was now watching over the wreck, said that the occupants were fine and had got a lift out to the next roadhouse. On our arrival we heard that they had encountered a road train coming in the opposite direction on the wrong side of the road, and had lost control in their panic. We still don’t know how the roadhouse manager got it back on its four wheels, but evidently he did because it later drove in to the roadhouse car park with surprisingly little damage beyond some chamfered bodywork and busted windows.

They were lucky. You definitely don’t want to run into a fifty-metre road train.

There are warning signs along the road for all manner of creatures, from camels to cows and kangaroos to ostriches. I suspect that many of these signs are just there to please the tourists, because for the most part the wildlife sticks to the safety of the scrub, but we did encounter a pair of emus that had come up to scrape dew from the tarmac. Seeing them in their native habitat, we realised that their hummocky bodies blended perfectly with the scrub, and it was perfectly possible to miss seeing a couple of metre-high birds if they were standing still.

On another stretch of road, I noticed a fallen log and pulled out to avoid it, and then had to swerve again because it was in fact a very large snake crossing the road and spanning almost the entire lane. I managed to avoid it, and I hope it got across before the next road train came through.

Large black crows picked up bugs that had been squashed by passing traffic, or clustered around the occasional road kill. Where there was a fallen roo, the feasting birds would usually see us coming from miles away and would take to the air well in advance, but on one occasion the birds seemed reluctant to leave. As we got closer, we realised that this time they weren’t crows, but instead a whole family of wedge-tailed eagles. As they struggled to get airborne, one of them revealed a wingspan wider than the fully loaded bike. We later heard tell of a motorcyclist who was showing off a long scar in the top of his helmet from the claws of an eagle that hadn’t quite got enough altitude in time.

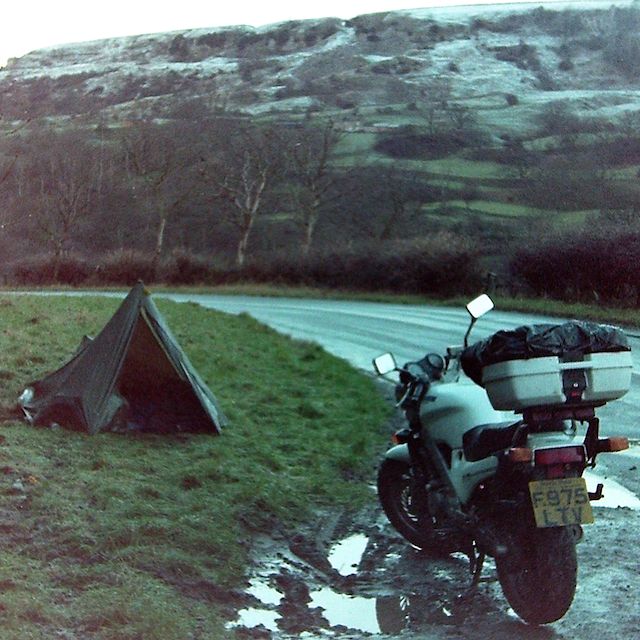

As we travelled further into the region, the cost of a room for the night rose dramatically. At Caiguna they wanted over $100 for a bed, but only $15 to use their camp ground (aka the open desert behind the rainwater tanks) so we set up the tent instead. We didn’t have sleeping bags, just a sheet and some felt blankets, and as luck would have it a cold front came through and the temperature dropped to three degrees, so it was bit chilly. Mind you, the stars were incredible.

After a few days, the roadhouses tended to blend together in our minds. Each had a pretty decent menu made up of frozen ingredients, jokey signs about tourists’ stupid questions, an endless supply of ‘I crossed the Nullarbor’ mugs, stickers and tea-towels, and – importantly – a well-stocked bar.

The cabins and camp sites were popular but we never had problems finding space. Once we’d watched the sunset there wasn’t much to do in the evening apart from go to the bar, and although we attended religiously every evening we were often surprised to find ourselves the only patrons. Most of the other travellers (road train drivers, grey nomads, the occasional motorcyclist) preferred to keep themselves to themselves.

We did get to talk to a few fellow-travellers. The road train drivers were working in shifts and trying to stay awake, moving goods and produce westwards and, usually, empty trailers eastwards. Sometimes they stacked the empty trailers up one on top of the other to save on tyre wear, and one driver explained how it was done. Apparently they back the first trailer up to a ramp, then reverse the second trailer up the ramp and on to first. Since they’re backing up a ramp, they can’t really see what they’re doing, and since all the trailers are the same size, there is zero tolerance for mistakes. Sometimes they miss and it falls off. We also heard about the fun they have moving mining machinery, because these stupendous machines are usually much wider than the low-loader trailer, with half of each tyre or track overhanging each side. Often the machine operator refuses to risk driving onto such a thin platform, and then it is up to the rig driver to fire up the unfamiliar million-dollar machine and ease it onto the trailer himself. Sometimes these fall off too.

The grey nomads were typically towing their caravans to warmer latitudes for the winter, and everybody else seemed to be driving Perth to Sydney as a sort of endurance feat; it is after all the complete width of the continent, passing through some of the most spectacular scenery in the country. We had passed a couple of lads on the road who were towing hand-carts on foot, but unfortunately there was no safe place to pull over for a chat. We did get to speak to a young student on a bicycle who said that he’d met them on the road and was a little jealous about how much food they were carrying, although apparently they were on a very tight budget and weren’t sure if they could afford to continue all the way to Sydney. The cyclist, a very pleasant chap, had decided to cycle across the continent on a whim.

The eastern stretch of the Eyre Highway runs along the cliff tops overlooking the Great Australian Bight. It was dusk when we passed the famous Bunda Cliffs, and the caravans were starting to circle and to jostle for prime sea-views. They always do this, but we could never figure out why, because they then seem to spend the rest of the night watching satellite television. We have considered doing a Grey Nomad trip ourselves (sort of a Brunette Nomad), and have even gone so far as to go to van shows and talk to caravan dealers. It had seemed to us that a caravan was very much like a yacht, and since we’d had such a ball sailing and meeting travelling yachties, we were keen to try the same thing on land. One of the great things about sailing in remote parts is that no matter how eccentric your fellow traveller, and whatever their walk or stage of life, they are almost always intelligent and interesting and, even if only for one evening, good company. Having attempted to similarly engage the caravanners on our travels, we had to admit that, by and large and with occasional exceptions, they were largely… not.

For the last day of our trip across the desert, incredibly, it rained. The roadhouses were full of celebrating station hands,

“How much did you get up at Kickatinalong?”

“Almost an inch!”

“Ah, good on yer mate. We had nearly half an inch at Dustbowlcreek.”

The road trains kicked up a heck of a spray, which made it essential to get past them but impossible to see if anything was coming the other way. Luckily the road train drivers are very aware of bikes – many are bikers themselves – and were very good about signalling when the road ahead was clear. We just kept the throttle open until we arrived at the quarantine checkpoint at Ceduna, officially the end of the Nullarbor and the start of the Eyre Peninsula.

The quarantine officer eyed our luggage and bright waterproofs with a jaundiced eye.

“Got any fruit?” he asked.

“No,” I replied, “no food at all”.

He stared broodily at Bronwyn, as if he suspected her of smuggling grapefruit under her jacket, then grudgingly nodded.

“Right, move along.”

We had crossed the Nullarbor.