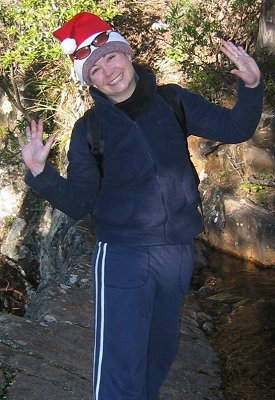

A hat and a waterfall

Having recently become addicted to the peculiarly Australian sport of “canyoning”, I jumped at the chance of a midwinter abseil down the Kalang Falls. Situated in the Kanangra-Boyd National Park in the Blue Mountains near to Sydney, the falls drop for a vertical distance of about half a kilometre into a deep canyon, after which you have little choice but to clamber the same distance back up along the aptly named Murdering Gully.

Cath, Carol, Andrew, Maria, Annie, Reinhard, Andy, Steve, Allan

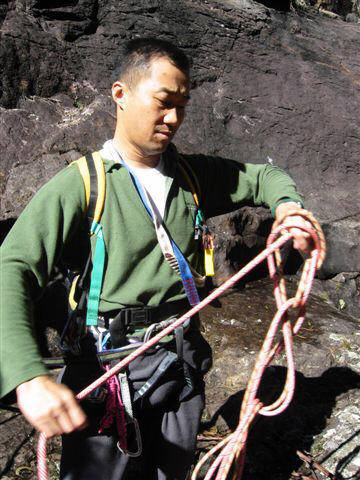

Thus it was that early one Saturday morning, a group of Kanangras black cattle, waiting patiently for the first dawn rays of the sun to evaporate the frost from their backs, were surprised to see nine enterprising adventurers heading out into the still darkened wilderness. Led by the highly experienced duo of Andy and Andrew, we planned to tackle the eleven abseils of up to sixty metres each, and then begin the three-hour scramble up Murdering Gully in the fading afternoon light, finishing up back at the top by mid-evening, hopefully still in posession of an eclectic selection of silly hats.

Annie goes over the edge

The sun lifted gorgeously above the canyon as we clambered to the head of the falls and began our first descent.

The falls drop in a series of steps, with enough room on one side or the other to abseil without actually getting wet; a so-called dry canyon, handy for tackling in the middle of the winter without the need for wetsuits and swimming. No problems with the cold here, however; soon we were stripping off the early-morning layers, chattering happily and basking in the sunshine during the inevitable waits for the ropes to become free.

A rest pause near the top of the Falls

On the third drop, we couldn’t find the anchor point. It soon became clear that an earlier landslide had changed the shape of the canyon, and it took an impromptu food break, some precarious hopping from rock to rock, and a good deal of sliding through uncertainly shifting underbrush before, about an hour later, we eventually found it and could continue down to the visitor’s book which was bolted to the cliff. The previous entry was about one month before.

Cath

Maria

The day progressed down a series of drops, giving fabulous views across the Kanangra-Boyd to the matching cliffs on the other side, and down to the sunny green treetops far, far below. Presumably in order to keep us entertained, Steve, who seems to have a remarkeable affinity to water, took the occasional impromptu bath.

Bushwacking

As the day wore on, and we sometimes found it necessary to descend on only one rope instead of two at a time, it became clear that what with the landslip and everything we were going slower than expected and would have to do Murdering Gully in the dark.

Murdering Gully from above

Not to worry, though, we had come well equipped with torches and extra snacks, and we still had our cool-weather gear from the frosty morning, so we expected to emerge at perhaps nine oclock in the evening. Then one of the ropes got snarled, and by the time we’d untangled it, we had three more abseils to do and dusk was already falling.

The Kalang Falls at dusk

Reinhard and Carol

Out came the head-torches, ranging from the positively ancient to futuristic hi-tec, except for Cath who had to borrow a hand-held maglite. Never mind, Cath, I said as I duct-taped it to her wrist. For the rest of the descent, she loomed periodically out of the darkness like a cyborg.

The head torches introduced another problem; what to do with Andys hat. This enormous wicker lampshade affair, all the way from Thailand, had bounced and scraped its way this far down, had been periodically retrieved and repaired, and now we had to find some way to carry it. Maria saved the day, volunteering to have it strapped to her pack, which gave her an interesting ninja turtle profile. The show went on.

The penultimate drop is, at sixty metres, the longest possible single abseil in the Blue Mountains. Well prepared, of course, we were actually carrying a sixty-metre rope rather than the usual fifty, which made it a bit easier, but we were also doing it in pitch darkness, which made it… interesting. I can absolutely recommend abseiling by starlight down the side of a waterfall. Suspended in space, I kicked out to bounce off a rockface invisible but for the small circle of light from my headtorch. Pausing halfway, and looking up toward the sky-spanning crystal arm of the Milky Way, I could see a pinprick of light that was Andrew far above, and turning my head, another pinprick of light far below that was Andy. All else was pitch darkness, apart from off to one side, the eery white thundering glow of the waterfall. Marvellous, just marvellous.

To commemorate the moment, as each climber reached the bottom, Andy solemnly handed them a lighted sparkler.

Finding the last pitch in the dark was nigh-on impossible. For a long time, most of us huddled on a rock ledge in the trees while search parties ranged through the forest below, little flickers of light appearing and disappearing between the steeply sloping trees. Time passed. We weren’t going to get out of Murder Gully until midnight. We thought about Lyn, waiting patiently at the top with the cars, and expecting us out by nine at the latest. There’s no mobile coverage out in the bush, but she had a car and sleeping gear, so we knew she was OK and hoped she wouldnt worry. Then finally, a triumphant call; the route had been found, but there had been another landslide, requiring the construction of a rope safety rail to clip onto as we crossed the rubble-strewn and uncertain slope, mere feet from the edge of the steep drop into the falls, before shimmying down a knotted rope and back onto the trail.

The last drop is entertaining. If you just abseil straight down, you end up floating in the deep plunge pool at the bottom of the falls; not ideal. What you have to do is get nearly to the bottom and then, shrouded in the thundering spray as the Kalang falls finally touch bottom, you have to swing and hop yourself round a big slippery outcrop, fighting against the weight of fifty metres of wet rope above you, onto a mossy little ledge. By torchlight. And, in Allans case, with a twisted ankle. But we all managed to stay dry; apart from Steve, of course, but he was getting used to that by now. Now for the strenuous but simple clamber out of the gully, and home to the waiting caravans.

It was not to be. It was, as I may have mentioned, seriously dark. We were at the bottom of a half-kilometre deep canyon, thickly surrounded by gum trees. Bush paths are always precarious things, it is hard to tell which are made by humans, and which by roos and wombats, but we figured we were heading in roughly the right direction – ie, upward – and so started to climb.

The going was tough, sloping at about forty-five degrees, and deeply littered with fallen leaves and branches. I was scouting ahead, following whichever of the many crisscrossing trails seemed to be heading most upward, and was beginning to get a little disillusioned when I found some taped markers on some trees. Hoorah! We were saved!

We climbed onward. Murdering Gully is supposed to take only a few hours at worst, so we should have been about to reach the main trail soon. Hours passed. We climbed. Midnight ticked by. The slope steepened. We climbed.

At one o’clock in the morning, we gave up. Clearly, markers notwithstanding, we were on the wrong ridge, but how to tell which was the correct one? We’d have to wait until morning. Australians have a word for this: we were benighted.

Tired but cheerful, we squatted on the 45 degree slope, passed around muesli bars and considered our situation. We were in dense bush without camping gear, but we had plenty of food and water, and enough spare clothes to go round for those who needed them. Despite the fact that it was midwinter, we didn’t expect the temperatures to drop much below zero. Our main concern was not for ourselves, but for the people waiting for us back in civilisation; Lyn in the car at the top, and Andrews wife in Sydney, who was expecting a were back call. An expedition into the bush is not to be treated lightly, and we had followed usual practice in leaving our itinery and instructions to alert the emergency services if we didnt make it back. One or both of the girls would certainly call the rangers if we didn’t show up by morning, and we didn’t want to cause an unnecessary furore. Still, there was nothing we could do about it, so we wedged a few fallen trees across some stumps to stop us sliding downward, and variously huddled together in a pile, or strapped ourselves to comfortable-looking trees, and dropped off to sleep.

Benighted

Before very long, the sun came up, and we lit a small fire and took stock of where we were. Or rather, we tried to; even in daylight it wasn’t really clear where we’d gone wrong the night before, and as we munched our way through breakfast we contemplated the unsavoury idea of climbing all the way back down to the valley floor, and starting up again.

At this point we started hearing cooo-eees of rangers on the cliffs high above; clearly one of the girls had sounded the alarm, and our fire had been spotted. Before very long, two SES Rangers turned up to see if we were OK.

Rangers Matt and Ewan

They seemed a little put out to find a cheerful, well-equipped group eating breakfast; we suspected that they’d been looking forward to an exciting spot of rescuing, but they bustled about anyway strapping up Allan’s ankle and handing out chocolate bars. They made an amusing pair, Matt a big cheerful guy who knew everything about the Kanangra-Boyd and imparted that knowledge accompanied by heavy swearing, and Ewan, younger and wiry, who seemed to have a personal ambition to carry the heaviest load out of Murdering Gully; he stuffed his pack with our spare ropes and fleeces, and would have been delighted to carry all our packs if we’d let him. Apparently he was locally famous for once lugging a car tyre all the way up to the top.

Most importantly, they knew the short cut out, which involved a bit of a traverse through the bush, but thankfully no downhill backtracking. As we walked, the pair regaled us somewhat wistfully with stories of the idiots they had rescued and the bodies they had carried out, admitting now that they would much rather that we’d been trapped halfway down the falls so that they could have done a bit of abseiling themselves.

Murdering Gully was a steep climb even in the winter sun, and we really appreciated a pause at a cave with a freshwater spring (we’d used most of our drinking water that morning to make sure that our fire was really extinguished; one thing the bush really does not need is more fires), and then, finally, we all climbed back up to the outside world.

It wasn’t quite what we’d expected…

A second truckload of rangers had set up an urn with tea and biscuits, and Lyn had brought a load of meat pies and sausage rolls, which was nice. However, we were also greeted by a brace of ambulances, a policeman, and a TV crew. Disregarding our somewhat amused protestations that we were all fine and had merely been caught out by nightfall, the TV crew homed in on Allan, now decked out with a nice big photogenic ankle bandage, and I guess it was a slow day because he ended up on the Sydney news.

Back at base

Thanks to Andy and Andrew for guiding us, to the ladies who worried at the top, and to the whole crew for being so buoyantly cheerful in what were occasionally adverse conditions. In addition, its nice to know that if we had really been in trouble, then there are all these dedicated, professional and above all cheerful people willing to give up their time to help. Thanks, then, to Matt, Ewan and the other SES rangers and emergency services at Kanangra-Boyd.